And the rest is implementation…

Implementation of services at the ground floor of organisations is not a merely administrative follow-up of the design process.

Implementation is considered a major challenge in service design nowadays (cf. SDN's global conference and the tenth year anniversary issue of Touchpoint (Vol 10 No 1)). (Un)fortunately, implementation is not just a challenge for service designers. It is a challenge for everyone who designs concepts, processes or strategies that imply change within organisations. In this blogpost I look across the disciplinary border in order to learn how to tackle this implementation challenge. Moreover, rather than taking the typical strategic perspective to implementation, I will focus on the ground floor of organisations and discuss the pivotal role of first line staff in implementation. I will do so by making use of my previous professional experience as academic and policy-driven labour market researcher.

Building on research on public policy implementation as well as own experiences as service designer I will point out the pivotal role of first line staff in the implementation of public services. First line staff are not only a key source of information to get to know clients and the organisation's ground floor culture. Service designers must also be aware of the direct and indirect impact that first line staff have on how services are distributed among clients and on how staff affect clients' motivation. I end this blogpost with a discussion on how successful implementation at the ground floor can be anticipated in a service design project. Though the focus is on first line staff in public services, many insights are equally relevant for private service first line staff.

First line staff

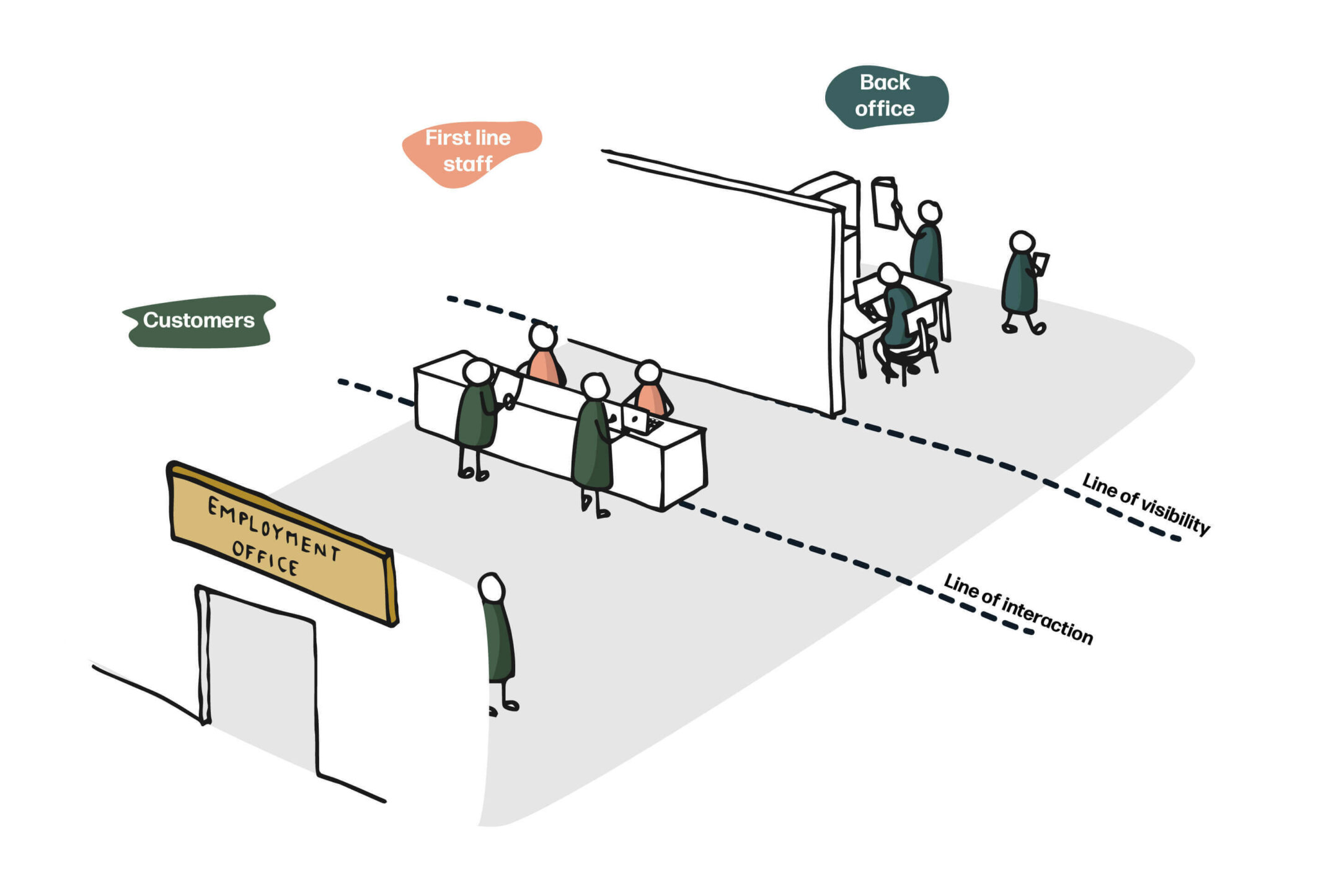

Service design is not just user-centred, but human-centred. That is, we do not only care about the needs and wishes of users, but of all key human actors involved in the service. Among them, first line staff who are in daily contact with users play a vital and pivotal role in service delivery. Think of nurses and doctors in hospitals, counsellors in an employment service, the receptionist in a library, a counter clerk in a bank. Next, I’ll discuss 3 main ways in which first line staff determine the success of the implementation of service concepts at the street-level. Some aspects of this key role will sound as an open door at first sight whereas you most probably not have been aware of others.

First line staff ‘effectively determine who gets what when and how’ ²

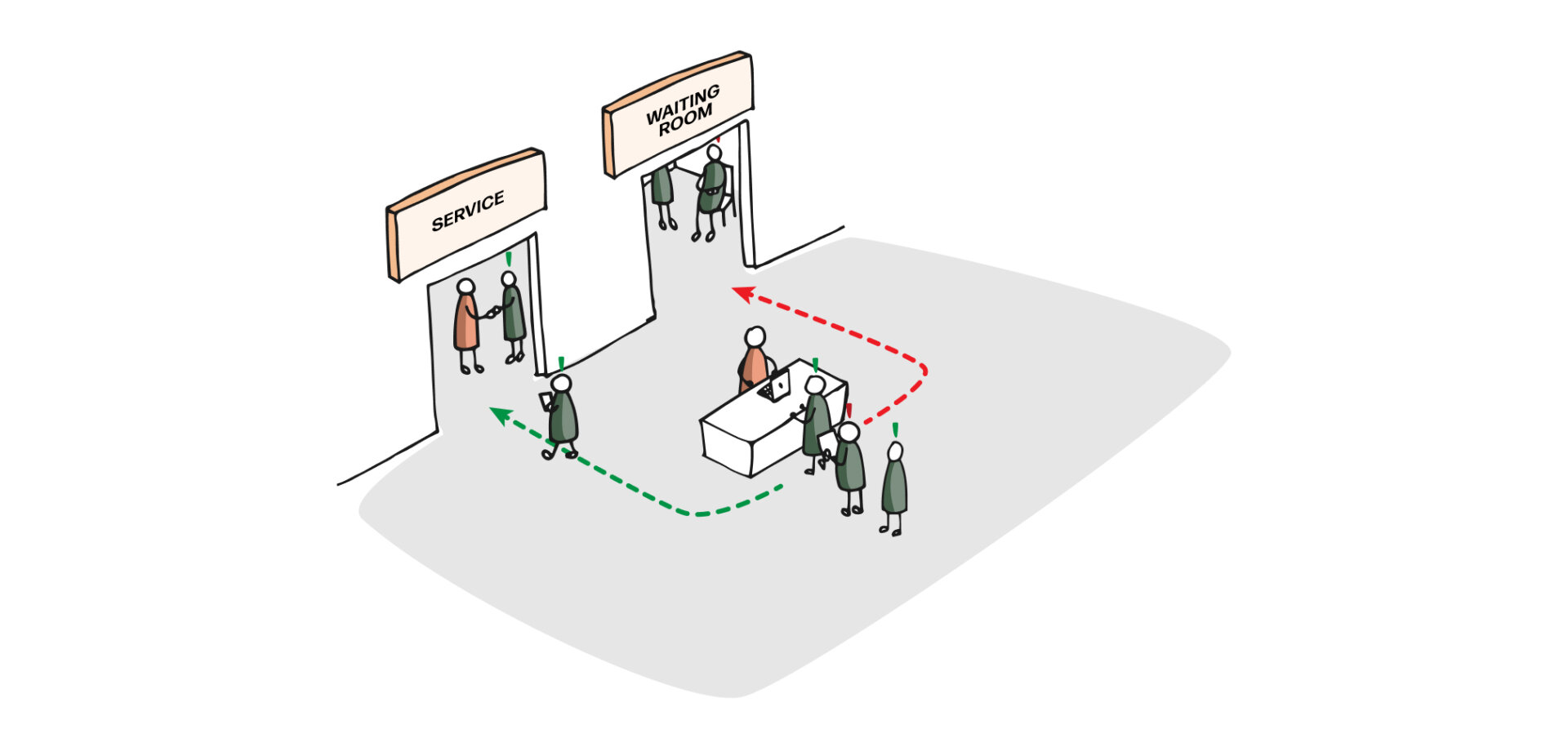

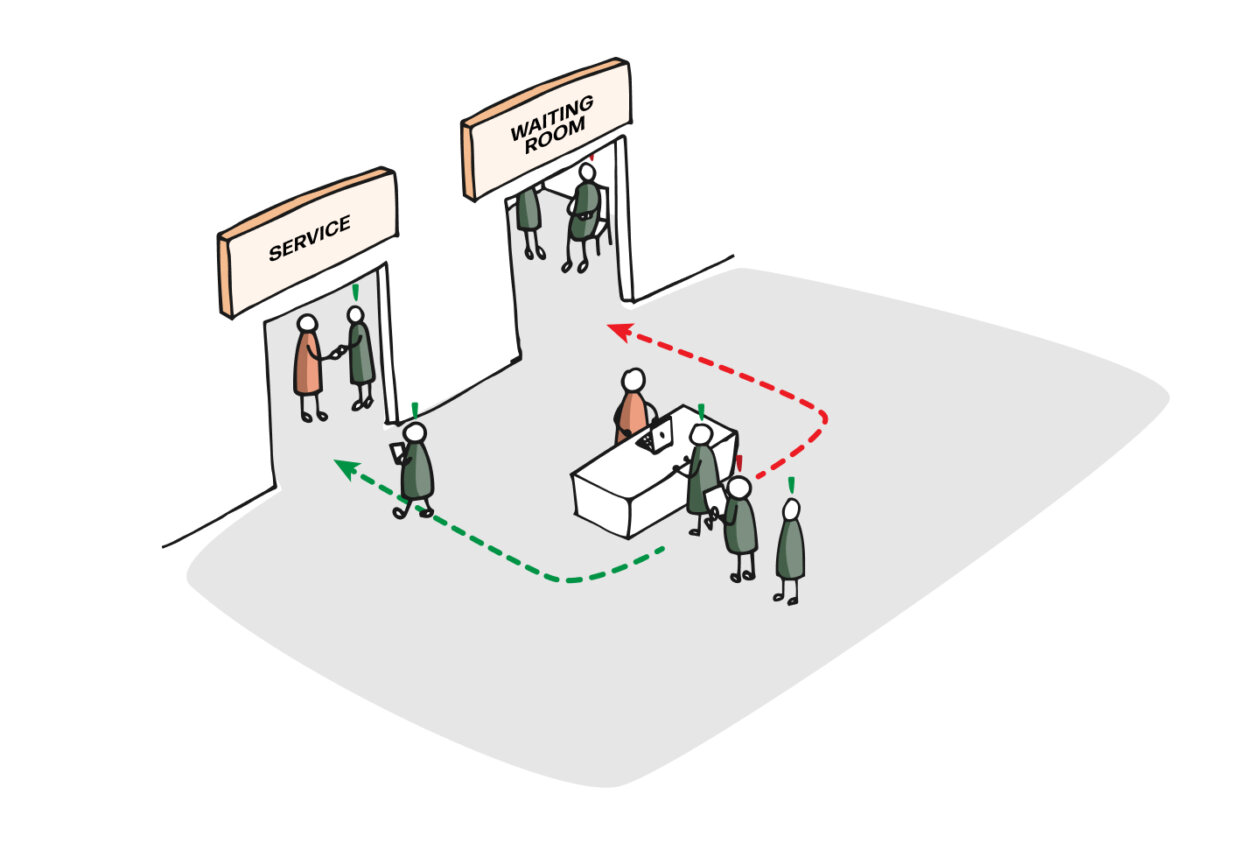

First line staff can play a pivotal role as gatekeeper. Rules can never foresee each individual case. Hence in order to be able to apply generic rules to idiosyncratic cases, first line staff are typically granted some discretion. Apart from that granted discretion, first line staff also may need to make their own assessments when rules are conflicting or because supply does not meet needs. Hence they ‘effectively determine who gets what when and how’.2 Evelyn Brodkin, professor in street-level bureaucracy, gives the example of a counsellor who must regularly meet welfare recipients to guide them and follow-up their eligibility.3 One of these recipients is a woman of whom the counsellor suspects that she might be victim of domestic violence. If one day the woman does not show up for a meeting, the counsellor can decide to further investigate this absence given the suspicion of violence or to sanction the woman right away for non-compliance. Apart from personal and professional values, factors like time pressure and what the counsellor is rewarded for most by her organisation will affect her decision.

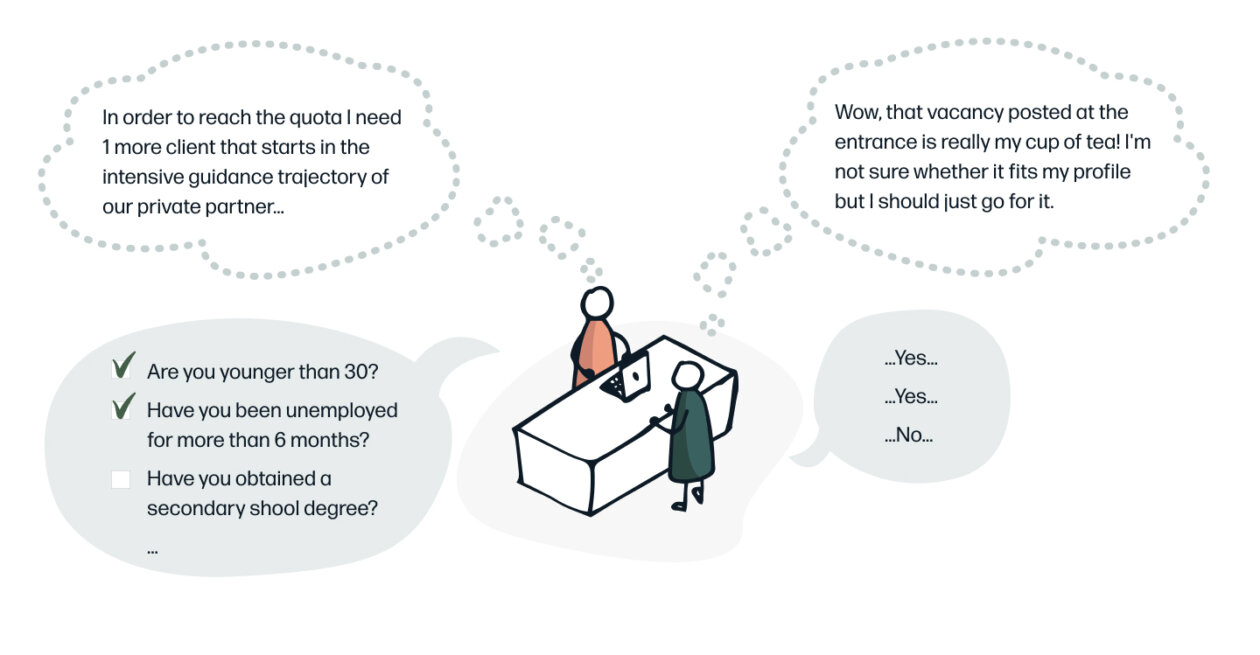

Research has shown that first line staff develop different ‘coping strategies’ to deal with their dilemmas.4 Examples are the rationing of services for the more ‘deserving’ clients, the act of ‘creaming off’ the most easy clients or ‘parking’ more difficult ones when supply does not meet demand. The use of quantitative targets to assess first line staff performance may aggravate these coping behaviours. Think for instance of the situation in which counsellors in an employment service are expected to weekly transfer a number of clients to a private subcontractor that guides and supports them to work for 6 to 12 months. When few clients fit the required profile counsellors will be enticed to select clients that match the profile approximately in order to reach the quota. Hence unemployed clients who need quick coaching get parked in a lengthy guidance trajectory.

First line staff are a service instrument in their own right

Finally, first line staff play a pivotal role because they have a direct impact on clients’ motivations through their interaction style. To illustrate this fact, let’s have a look at how a young guy defines how he wants to be approached by the employment service counsellors.

A good counsellor, gosh, I have not dwelled upon that yet... A good counsellor, yes someone who lets you talk, who then talks and who then deliberates together. (…) Someone (…) who not only looks from the perspective of their work but also from the perspective of what is possible in your eyes or your experience. Yes actually (…) in particular someone who can listen but who also can proof that they are there for you. (…) Yes, something like that I guess (laughs)

In my PhD study5 I showed that clients who experienced such an ‘autonomous supportive’ approach rather than a ‘controlling’ approach were more willing to engage with the employment service and would engage more actively. The distinction relates to the degree to which clients experience that they ‘want’ to engage rather than that they feel forced to do so by external (sanction, reward) or internal (guilt, shame) pressure factors. The importance of the experience of autonomy for human motivation has been shown in different studies building on the psychological self-determination theory. Thus, for service designers it is important to be aware of these different styles and if change is required in first line staff’s approach to clients.

The reasons why staff apply one approach or another may relate both to personality as well as to the circumstances in which they work. This implies that caution is required in how first line staff’s behaviour and decisions are monitored and assessed by the organisation. Under the premise of New Public Management more and more organisations have introduced quantitative output targets. If these are not accompanied with a monitoring of the quality of service delivery there is a risk that first line staff develop a controlling rather than an autonomy supportive approach. To come back to the previous example of the employment counsellor who must transfer a fixed amount of clients to a private partner each week: the more this counsellor experiences pressure from the target, (s)he might be less open to the clients’ perspective and would rather push the client towards the private partner’s offer.

First line staff are a key source of information on users and the street-level of the organisation

First line staff are a key source of information during the service design process, both on their clients, their working conditions and the ground floor culture. Since first line staff are in daily contact with clients/users, they are very well aware of clients’ characteristics and the circumstances in which they live. These are crucial insights to understand the diversity among clients, the motivations of clients to engage with a service, the obstacles encountered by clients in obtaining a service successfully … In a recent track for a Belgian museum the inclusion of the staff at the ticket counter proofed vital to discover the limits of the current website. Thanks to their daily experiences we found out that many museum visitors need more up front information on which sections of the museum are temporarily closed due to the set up or break down of a temporary exhibition. Though, attention must be paid to the fact that first line staff might have developed stereotypical accounts of their clients overtime (for instance to deal with complexity or a lack of resources).

In addition, first line staff are key informants on the conditions in which services are delivered to clients. First line staff often offer services of which supplies do not meet demand or of which the quality is affected by factors beyond their control. Hence, first line staff may have the feeling that they are at the frontline. Especially if they feel insufficiently understood and backed by higher level management. In some cases the frontline must be understood literally. Drivers of the public buses in Flanders regularly strike to draw attention to the daily violence they experience. The Belgian railway company just launched the interactive #StopAgressiesNMBS campaign to reduce aggression against its first line staff in trains and railway stations.

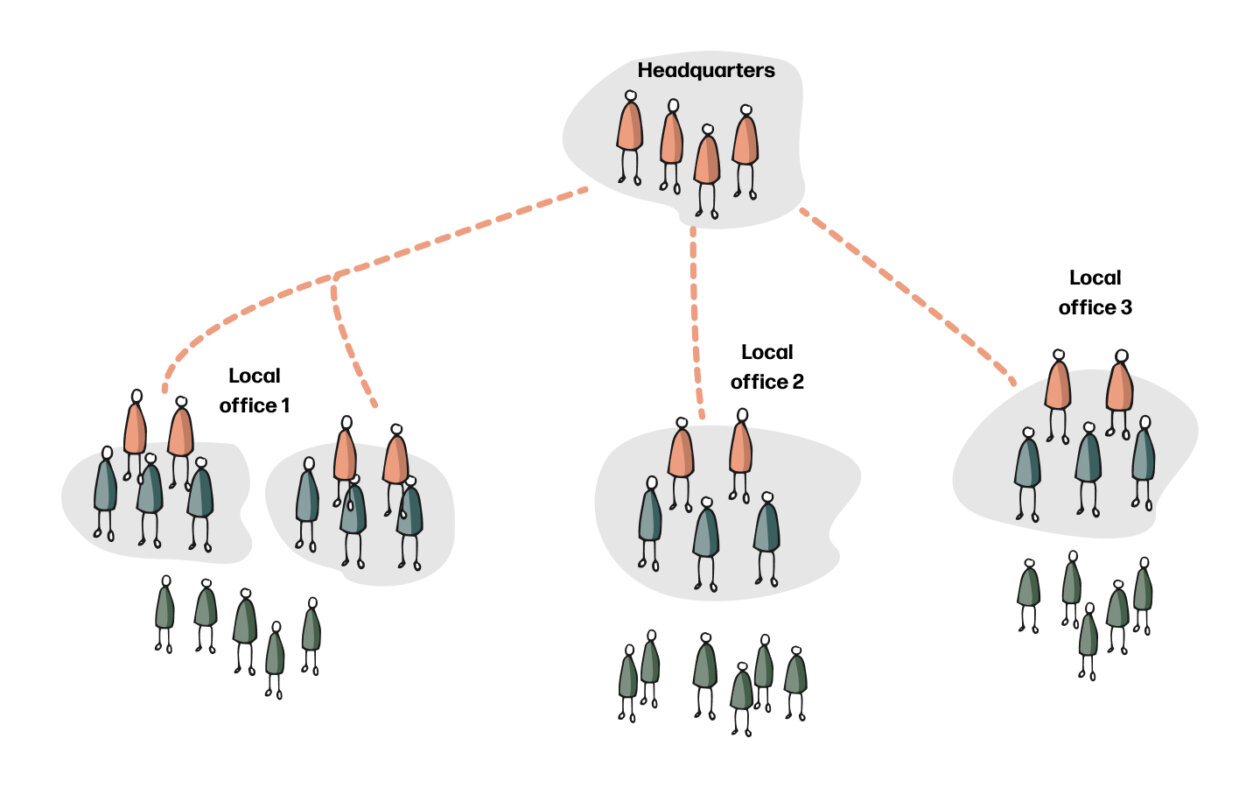

Furthermore, first line staff are key informants on the ground floor culture(s). As Weisser, Mager & Jonas point out in Touchpoint, successful implementation hinges upon a thorough diagnosis of the organisation’s culture. One should be aware that there might be not just one culture, but different cultures across and within the organisation’s layers. The specificity of the tasks, expectations, stakeholders, remunerations … of first line staff (segments) compared to other staff within the organisation may create different cultural bonds and different interpretations of the organisational identity.

Anticipating successful street-level implementation in practice

With what we know now, how can we as service designers anticipate successful implementation at the ground floor/first line in different stages of a service design trajectory? Here are some suggestions.

- Persona: first line staff are key informants when it comes to identifying and constructing relevant and in-depth persona. Yet participating staff members must also be challenged to unveil their stereotypical accounts.

- ‘First line staff journeys’: Through observation, interviewing and co-creation we can better understand the challenges and working conditions of front line staff in delivering services and see how these affect their work. This can be done in 2 ways: 1) the customer journey can be enriched from the perspective of first line staff; 2) a first line staff journey is developed that maps the journey of a daily routine or a more long term recurring cycle in first line staff’s work.

- Co-creation of a successful interaction style: by use of role play with clients first line staff can explore and test the success of different interaction styles to engage clients in service delivery. These insights can be used in a later stage to train staff.

- Service design blueprint: first line staff can shed light on where dilemmas will arise to prevent the development of counterproductive coping strategies

- ‘First line testing’: apart from testing new concepts with users, it is important to also test the delivery process with first line staff: do they consider the service and their role in its delivery as desirable and feasible and how could this be improved?

- Monitor implementation behaviour during testing and once the concept is launched. Be aware to not only look at quantitative outputs but also at the quality of first line staff’s work.

- Adapted training and intervision: Based on an analysis of what first line staff’s fears and worries are regarding implementing the new/improved service concept, adapted training modules can be developed to help them overcome and deal with those fears and worries. Intervision implies that first line staff come together to exchange thoughts and experiences related to real cases to learn from each other and align their approach. At this years SDN Global Conference I participated in the workshop ‘Facing your fear of the citizen’ workshop (see picture) in which Angela Kelleher (Cork Council’s service design centre Service rePublic) guided us through a stepwise approach to support first line (and higher level) staff to become excited to and feel comfortable getting in touch with clients in new ways. Starting from persona we identified the web of fears they are confronted with and investigated the different ways in which those fears could be addressed.

Conclusion

To conclude, when services or their delivery fail first line staff are often blamed for thwarting implementation and subverting goals. Such a topdown approach on implementation wrongly supposes that implementation is a mere administrative follow-up of the design process. In reality first line staff are confronted with unresolved dilemmas resulting from conflicting rules and gaps between demands and resources. Successful implementation requires that service designers gain insight in the circumstances in which first line staff work and how these affect their accounts of and approach towards clients. I ended this post with a handful of possible strategies to anticipate successful implementation in different stages of the service design trajectory.

I look forward to hearing from you how experienced working this way with first line staff in your projects and how these or other strategies have contributed to successful street-level implementation!

Resources

- This is the title of an article by renown policy scientists Michael Hill and Peter Hupe on the challenges of implementing public policies. There key message is that implementation should not be considered as merely a technical follow-up of the policy design process. Hupe & Hill (2016), ‘And the rest is implementation.’ Comparing approaches to what happens in policy processes beyond Great Expectations, in Public Policy and Administration, 31(2): 103–121.

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2011), ‘Putting Street‐Level Organizations First: New Directions for Social Policy and Management Research’, in Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(suppl2): i199‐i201.

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2016), 'Street-Level Organizations, Inequality, and the Future of Human Services', in Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(5): 444-450.

- See for instance the seminal work by Lipsky, M. (1980/2010). Street Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. 30th Anniversary Expanded Edition. The Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY. See also: Hupe, P. Hill, M. & Buffat, A. (2015), Understanding Street-level Bureaucracy, The University of Chicago Press. AND Hupe, P. (forthcoming), Edward Elgar Handbook on Street-level bureaucracy Research: The ground floor of government in context, edward elgar.

- Van Parys, L. (2016), On the street-level implementation of ambiguous activation policy. How caseworkers reconcile responsibility and autonomy and affect their clients' motivation, Leuven: KU Leuven.