Where does the designer stand?

Being a designer in a co-creation process is sometimes like walking on a frozen lake, slippery in some parts and thin in other parts. Clients might enter a project with different expectations or thought they were buying a specific end-product rather than a design process. As a designer it can become difficult to see where to stand or what can be emerging cracks in the co-creation process. In this article we’ll go over some of the threats to the co-creation process, discuss possible strategies as to what a designer can do to deal with them and reflect on the position of the designer.

Note: this is by no means an exhaustive list of threats to a design process.

Before going to these threats to the co-creation process, these should be read differently depending on whether you’re a designer or a client wanting to integrate the co-creation process in their modus operandi. The former will recognize situations from previous experiences in co-creation and might even learn about situations they could encounter, the latter could identify factors that will make it more difficult yet not impossible to integrate the co-creation process in their way of working.

Overly defined brief: Instruction manual

Let’s get started! … or not. Sometimes a client asks for a co-creation process as it generates the impression of a democratic process (especially important in policy related projects), but the brief doesn’t leave much room for co-creation to occur on a level where the participants feel their input will have impact. In this case co-creation can be seen as policy lubricant for decisions that have been made already, but will be difficult to swallow.

In an urban planning setting this can present itself through severe interventions in a neighbourhood, in which the neighbourhood has little input, but their input is requested on the small park which will be created. This often creates a very tense setting in which the designer is seen as a distractor to create the impression of a democratic process. As a designer it’s important to recognise the overly defined brief and decide if you want to engage in this process. Once you’re in the process and you feel trapped it could be important to keep the long term perspective in mind.

If you do exactly what the client asks, will you jeopardise your credibility as a designer in a co-creation process? If you please this client, would you be able to show them the benefits of a co-creation process for their organisation? So what is a designer to do? If one has the option to refuse the assignment, this could be considered, but this also means that the designer at that point relinquishes all possible control over the end-product and all possible options to still create an opportunity of a better outcome. One should then also consider whether one is up for a mission that could lead to quite a bit of frustration on the end of the designer.

"The company owner doesn't need to win. The best idea does."

- John C. Maxwell

Lack of vision: show us the way

In some cases a brief can show that a client doesn’t really know what they want. There might be a lack of detail, popular terms might be used a bit out of context and the whole thing might read a bit incoherent and lack definition. The causes for this can vary, in a governmental context a policy might be ambiguous not to offend governing partners, in a company setting this might be due to institutionalisation where innovation has systematically been halted and the initial vision has become outdated. A major threat to the design process here is that there is a lack of limits, the client might have unrealistic expectations of the outcome and you might end up spending a lot of time counselling the client to deal with unmet expectations.

Additionally a lack of vision could also be the result of being stuck in a rusted behavioural pattern which simply doesn’t work anymore but is still a source of comfort to the client. In this case you risk spending a lot of time on counselling the client through their fear of change. All of this leads to a very inefficient co-creation process. If you have the possibility, you could try to organise an exercise in which goals for a specific project are defined. However, if the lack of vision is present throughout the entire organisation, such an exercise will only have a limited impact.

"The only thing worse than being blind is having sight but no vision."

- Anonymous

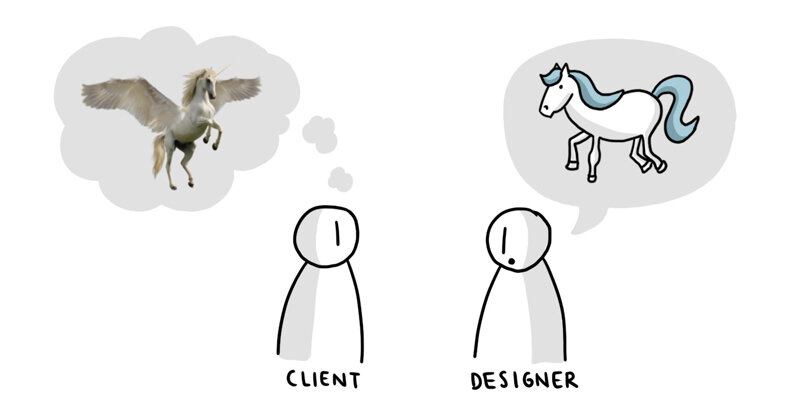

Unclear expectations

Related to the previous threat, yet this could be related to both the client as well as the designer. If a designer expects the client to have properly read and understood the proposal without further confirmation during a one-on-one meeting, the designer might be in for a rough ride. The client might not have made the right preparations and the project starts with a delay or a very stressed client trying to get everything sorted in the last minute. This can translate into a kick-off meeting with a lot of frustrated people. It could also mean that the client has mentioned incorrect expectations to the other participants of the project or sponsors of the project, and is unwilling to change those expectations. Additionally, a client might have read the proposal, but the cultural/technological gap between you and the client is very large and the client simply doesn’t understand what they signed into.

Besides a kick-off meeting with some frustrated participants, you mainly risk that the client is not ready for the solutions you’re going to present or that the client becomes very anxious as they don’t know what to expect anymore or to communicate to the sponsors of the project. One way to deal with this kind of situation is to meet up with your contact at the client, assess the situation and set the expectations clearly, as well as giving the client some time to prepare. It also allows you to assess whether the client described the state of affairs correctly in the brief, and whether the planned project can still be executed in its current form. Getting in contact with your client as soon as possible might also prevent your client from losing face during the kick-off meeting.

There’s no team

Just a bunch of people. Depending on the project and the expectations of the designer, this can lead to some real issues. A designer can assume that the people in the team know what their and each others role is. In newly assigned project teams this might not be the case, for instance in governmental contexts where statutory employees are assigned to a new position after implementation of a new policy, or in contexts where the kick-off is one of the many meetings the employees have and they don’t know what they’re actually doing there. This means that the team might not be a team yet and will have to deal with the growing pains of a new team, communication might be absent, expectations unclear, the leader might still have to establish authority, there might not be a clear structure. As a designer it might mean that you’ll have to include a team-building exercise in your routine and/or give the team some time to sort things out first. Don’t underestimate the impact of meeting with your contact at the organisation before the kick-off and guiding them through the process of selecting and informing the ideal candidates for this project, assuming that your client has sufficient knowledge of this might come to cost you along the way.

Additionally, not everybody might be as extraverted during a workshop as the average participant. Introversion could be a possible factor for this and should therefore not be interpreted as a problem amongst team-members. Classical exercises like brainstorming can make these participants suffer from production blocking. An easy solution to this problem is to let every participant write their ideas down and letting each participant state all of their ideas one at a time.

Hierarchy! Or lack thereof…

You might have experienced this one, your project is going like a train, but at some point a decision needs to be taken and the project comes to a standstill as hierarchy needs to be respected. If the decision is finally made every subsequent move has to be checked with upper-level departments. What started out as a co-creation process has just turned into a top-down decision process. This can suck the life out of the project and its participants. The opposite is also possible, a manifestation of anarchy has become apparent and power struggles start occuring in the organisation. There is very little to do in this case but to become aware of this, take into account possible triggers for conflicts or discuss the situation if you feel comfortable/capable of doing so. There might be need for other specialists to solve the underlying problems. Furthermore, this might not only play at an organisational level, but also within the project group. If there is not clearly assigned team-leader or rules to allow for a democratic decision process there is a high chance of dominance struggles or chaos to occur.

"The worst enemy of life, freedom and the common decencies is total anarchy; their second worst enemy is total efficiency."

- Aldous Huxley

Is there anybody missing?

Very often there is. Either it’s the decision makers, but also essential collaborators or critical voices. When decision makers are missing you run the risk of landing in the above mentioned standstill or a complete rejection of the solution once presented to the decision makers. If one or more essential collaborators are missing, it could delay the project, create a solution low in impact or make implementation very difficult once the solution is decided on. At its most subtle level we find the lack of a critical voice. In some cases this can be a strategic decision, in other cases it can mean that there is simply a lack of critically thinking collaborators. In the latter case it’ll entail that you as a designer will have to be very critical of the input and thought processes occuring in the team. One way to make this explicit is by starting the track with a stakeholder mapping exercise which could provide the opportunity to present some critical thoughts about the constellation of the group. Additionally, it is possible that the entire team might not be suited to the tasks at hand. When this is discovered along the way this should be discussed with the client and made clear that this jeopardizes the outcome of the project. Ideally the constellation of the team should be discussed before the kick-off to ensure a fluid start.

Is there anything missing?

There might be. It could be sensitive data, in which case it’s advised to deal with this in a discrete manner with your contact at the client and see how this can be dealt with and might impact the design process. At its most uncomfortable level, there might be hidden motives that you only become aware of during the project and you’re in essence ‘meat in the room’. At that time the trust relationship between you and the client will have likely received a serious blow. One strategy to deal with this upon discovery is to approach it from a constructive point of view. Motives might be hidden, but that doesn’t mean they have to be negative or that the client has bad intentions. Discussing the situation with the client might shed more clarity on this matter, it is important not to accuse the client in that situation.

The designer position is undermined

In some projects the role of the client might not be clear, are they needed for input or designing along with you? Some clients will assume that they are also designers in this project and underestimate the role and contributions of the designer in the project. This can be problematic when the designer easily steps forward as an expert.

How to prevent some of these situations

Branding can play an important role in this. Taking a strong position on design will make it clear to many (not all) clients what you’re about. This can be done by writing down a clear mission statement or manifesto as to what design means to you and to which principals you adhere. Additionally, by behaving in accordance with your mission statement, you can build up a reputation which sets clear expectations towards clients.

As mentioned before, it’s important to get together with your contact at the client before a kick-off meeting and assess the situation so you can anticipate certain issues. Make sure the client has some time between that meeting and the kick-off meeting to make the needed adjustments for the project.

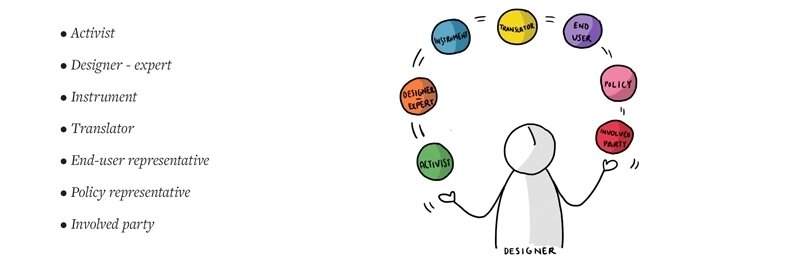

Finally, disclose your position during the project. At the start of the project you can mention that you might have to take up different roles throughout the project, you can be an instrument of the client at times, but also act as devil’s advocate at other times. In case a client is having some issues seeing things from your perspective or different perspective, a role playing exercise might help. In a governmental setting where a policy might lead to controversy, it might be interesting to have participants take up the role of the activist. Different positions are listed below, but one is especially important to mention at times in a project, namely that of the designer - expert. Some clients see themselves as designers - experts and aren’t receptive towards new perspectives or ideas you bring along with your experience. Add to that that some designers don’t feel confident enough to take up the role of the expert, and you might end up with a product that doesn’t meet the needs of the end-user. Explicitly taking up the role of the designer - expert sometimes can make it clear to both clients as well as yourself that you are an expert.

What is the current position of the designer?

There has been increased interest in design thinking methodology and co-creative processes in different sectors such as the public sector, finance, healthcare, retail, marketing, sports, administration, etc. Design thinking methodology is progressively appearing in education curricula as a necessary skill for the future. This also requires designers or design team to not simply rely on design skills but also on facilitating skills. The latter is in some cases comparable to a therapeutic process where a client will be made aware of their environment by being more perceptive of it and design solutions with that environment in order to create more synchrony between what the client and their environment want. In the case of co-creation this could involve end-users sharing grievances about a service or employees providing valuable feedback and possible solutions to the heads of their organisation.

A designer in a co-creation process will have to become somewhat of a polymath by mixing skills acquired from social science research, therapeutic processes, design and possibly philosophy in order to produce solutions which will have a higher chance of implementation. It will require designers to become more aware of the context in which they are operating and the threats which could harm the delicate co-creation process. The designer will sometimes need to take a step back and assess what’s going on, what that feeling might be that’s making them uncomfortable in a particular project and use that information in a co-creation process in order to drive a sometimes needed adaptation.

"If the immediate and direct purpose of our life is not suffering then our existence is the most ill-adapted to its purpose in the world."

- Arthur Schopenhauer